Category Music

Published February 4, 2026

Nevada, by Kirsty Harris, oil on board, 2025

Story scent: old church basement

Story flavour: copper

Play on repeat while reading: “MN4-D2-4.1“, by N|O|E|W|A

On a cold, rainy night in November, I sat in the old Fishermen’s Chapel, near the shore of Leigh-on-Sea. Train cancellations sent a constant stream of cars rushing along the road just outside, and a chill hung within the main room that wouldn’t leave my bones. The organ sat silent, the Bibles and songbooks were all put away, and there were no worshippers in sight. The music of mass would not be ringing out through the stained glass windows tonight; instead, something far stranger: a concert of improvised, predominantly electronic music.

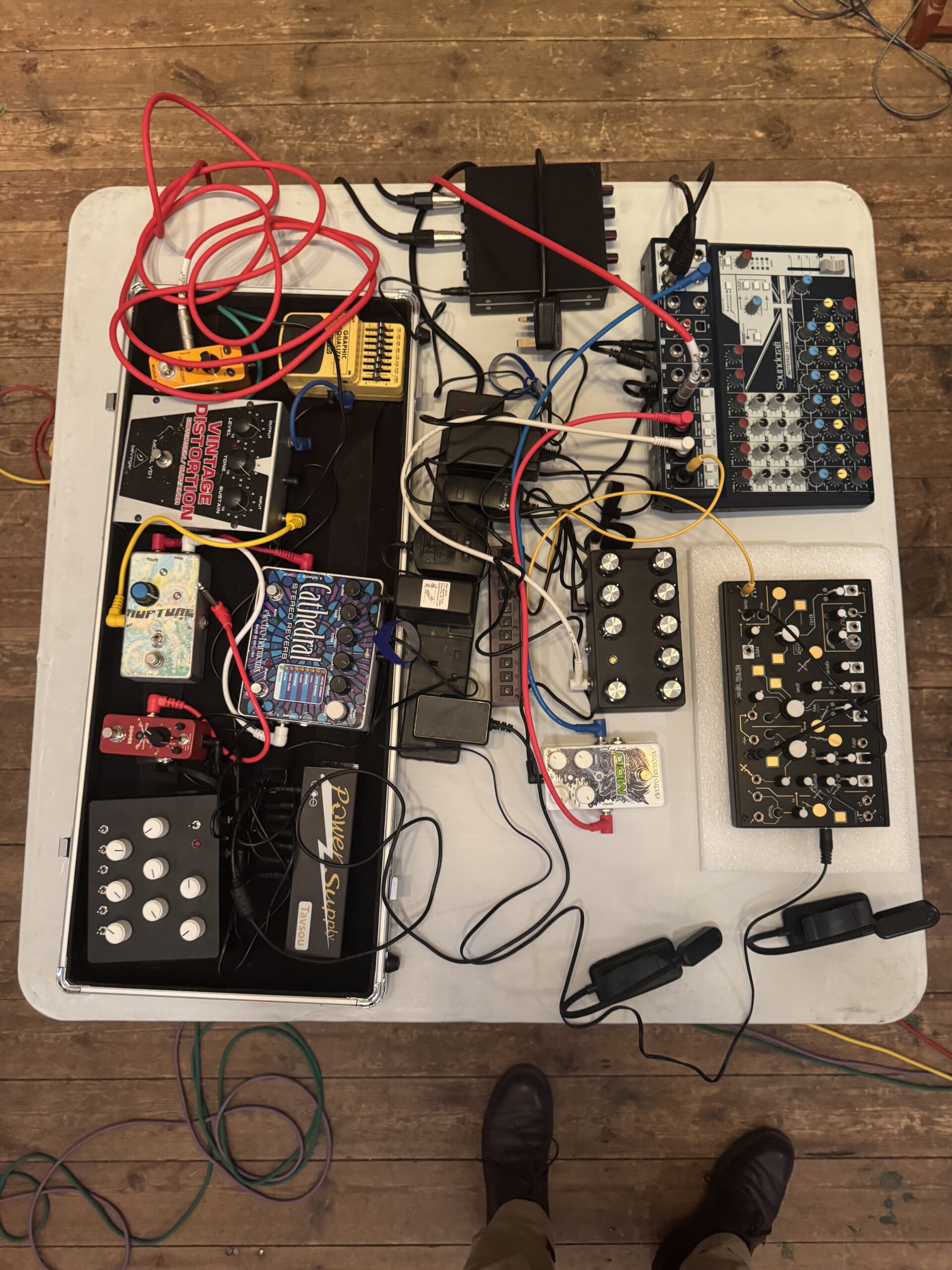

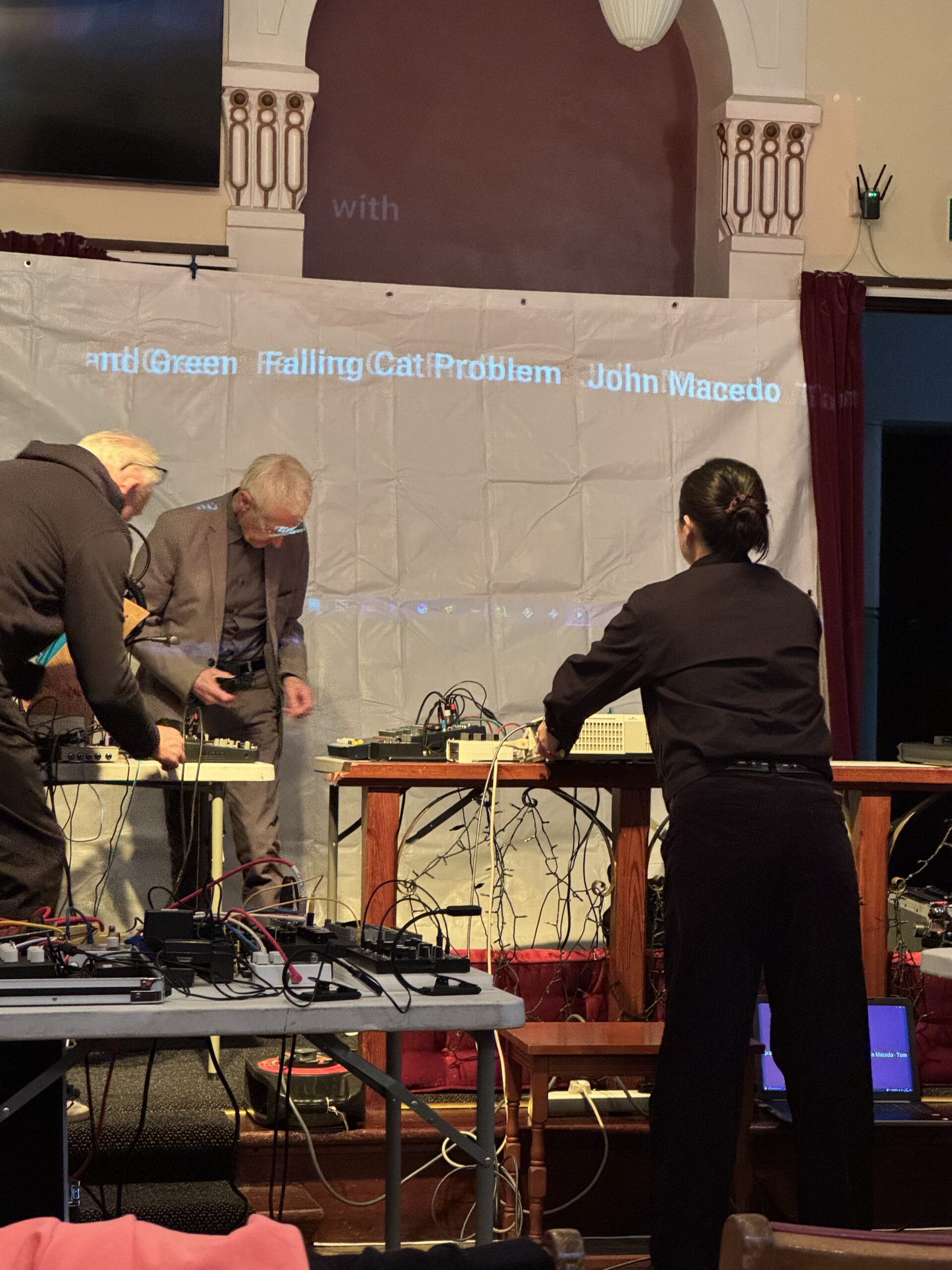

At the front of the room where sermons would normally be delivered and choirs sing hymns, an eclectic group milled around six 1m² foldable tables, setting up what to the layman might look like the controls for the Starship Enterprise; countless flashing lights, knobs and buttons on panels with cryptic symbols all over them; wires snaking over everything and esoteric terminology being thrown around in every direction. A druidic, impressively bearded man plugged something into his setup and the church was suddenly filled by a low, menacing droning sound. A few of the others nodded approvingly. Meanwhile, Levente Dudaš, the night’s organiser, busied himself with his own setup at one of the front tables.

I first came to know Levente, not as a musician but as the father of my girlfriend. He is a tall Hungarian man with a long grey ponytail, goatee and strong brows that remind me sometimes of a warlock. On our first meeting, we shook hands, and in no time at all, I was knocking back shots of pálinka around their dinner table, which is excellent for those first-time-meeting-the-parents nerves. With the booze warming my insides, I figured the best way to break the ice was to bring up our shared interest in electronic music, specifically modular synthesis, which I understood he’d been a longtime practitioner of. Levente’s eyes immediately brightened at the mention, and the next day we locked ourselves away in his studio space, forgot about our significant others and completely lost ourselves for several hours as he attempted to teach me the basics of patching a synth—something I’d only ever seen done on YouTube videos.

What the creative world of modular synthesis means to me has changed over the years. At first, it was just a wide-eyed fascination for a type of music-making I found deeply intimidating. But over time, especially as I’ve started to build my own synthesiser collection, it has developed into an at times spiritual and therapeutic practice for me, one that makes me feel a part of one of the more eccentric and experimental corners of the contemporary music scene that Levente happily occupies. More importantly, it’s opened my mind to alternative methods for practising creativity, which have challenged many of my assumptions about what “legitimate” forms of art-making even are.

Particularly now, as AI begins to seep into the art sphere in both ominous and intriguing ways, I’ve found this type of music and creativity useful, not only as a reminder of how clearly irreplaceable human creativity is, but also as a potential framework for understanding how emerging and disruptive technologies, like AI, can be better reckoned with as an artist.

Konsztrukting ELEKTRONIK Soundz EVENING NINETEEN

Modular Synthesis, For Those Who Don’t Know

Levente’s studio is in a small room on the second floor of their house. Though there’s a fold-up bed to one side, almost every other function of the space has been devoted to music. At every turn, the eye meets some new gadget or contraption, many of which I’ve at one point or another added to my own wishlists while online shopping, but never had the chance to see in the flesh. On a desk at the centre of the room sits his modular rig, which, on my first visit, he encouraged me to “just try it out” and experiment with. Like sitting behind the wheel of a car for the first time, no amount of conceptual preparedness makes you truly ready for the act of patching a modular synth. Whatever I thought I knew went straight out the window as I inserted a wire into one of the ports, and absolutely nothing happened. I tried another port and nearly ruptured our eardrums with a horrible droning sound. I looked ashamedly at Levente. “It’s good, man,” he smiled, “this is part of the process.”

The world of music has no shortage of nerdiness (which I say with love), but the world of modular synthesis, I’d wager, gets pretty close to the peak in terms of niche obsessions over equipment, complex terminology and openness to experimentation. For those who have no idea what I’m talking about, a modular synthesiser is basically a blank canvas in terms of opportunities for sound creation. A typical synth locks you into certain characteristics and methods for manipulating sound that have been hardwired to work in specific ways. They are complete, closed systems that can be modified by external effects but are designed to essentially run on their own without modification. Modular synths, however, are just that, modules that can be swapped in and out to change the kinds of sounds you want to make, allowing for most if not all of their attributes to be rewired and recombined—or “patched”—using cables. Any module that uses the same basic architecture (Eurorack is the most common) is compatible with any other module, allowing for almost limitless sound and melody creation. For better or worse, you’ll almost never get the exact same sound twice when you sit down to compose something and (especially as a novice) you’ll probably have no idea how you even made that sound in the first place.

For a certain kind of person—myself and Levente amongst them—it’s the kind of thing that scratches a very specific creative itch, with the perfect blend of technological wizardry, lots of flashing lights, always feeling like there’s something else out there you’d like to buy, and a certain mystical unknown element that tends to yield plenty of surprises when creating sounds.

Modular synthesis opens the door for another kind of creative process— generative music. This is music creation where, through a series of presets, you create an algorithm in which a sound or melody may not only form but also evolve over time without further interference. Rather than composing every single note in a piece of music, you’re basically pushing a rock down a hill and, based on the rock and hill you chose, the effort of your push and other factors, you create a context for its descent, though you can’t entirely predict what the outcome will be.

It’s in this aspect of the unknown where I find much of the sheer pleasure and fun in making generative music as well as modular synthesis overall. Nothing beats that feeling of hearing a sound or melody you’ve created, not having any idea how you got there, and thinking, “Wow, that sounds like nothing I’ve ever heard before!”

Now is probably a good time to set the record straight that I am very, very far from an expert on this. Modular synthesis and electronic music in general are worlds that just go deeper and deeper, and I am a relative newcomer with an immense amount to learn. To my eyes, the crowd setting up in this church for Levente’s concert had that seasoned confidence of soldiers who are coming back from their third tour on the front, while I’m just in from basic training. Hyperbolic that may be, I was struck most of all by just how much I didn’t know and desperately wanted to learn.

Weirdness and Art

This gathering of musicians in the church is part of Levente’s Konsztrukting Soundz series (https://konsztruktingsoundz.co.uk/), where a lineup of musicians play roughly 20-minute sets in which they must adhere to certain performance criteria, first and foremost being that their performance must be entirely improvised. In some cases, the musicians have never performed together or even met until the night of the concert and must discover how they collaborate in real time during the set.

It’s always a good time, and I can safely say you’ll have never heard anything like it before. Music styles vary widely. You might hear a musician playing homemade bagpipes or another feeding a traditional Chinese flute through a series of electronic filters and pedals. Some performances veer more into noise, sample-led loops or Dada-esque compositions that I struggle to categorise at all.

For example, in the second set of the night, two performers who go by “Falling Cat Problem” blasted the audience with a cacophony of crackling noise that was so powerful and unrelenting, several audience members were forced to plug their ears. For me, the experience became trance-like.

In the next performance, the lady with the improvised bagpipes played loud, blaring sounds while her co-performer “sang” a series of strange, halting yelps, which had an altogether different effect on the audience from the previous set.

This concert series resonates with me because I find in it a wonderful kind of free creation and eccentricity I personally feel is missing from a lot of mainstream art spaces. Many galleries and other cultural spaces I visit in London feel to me a bit cold and aloof, or just far too commercial. They seem more concerned with the appearance of deep conceptual rigour while serving what is financially demanded in the art market and what is easily associated with other artists who have already found success. To me, there’s less emotion, less heart and less earnestness in this kind of art and the community surrounding it, where networking, return-on-investments, and market performance make it all feel like just another commodity to be bought and sold.

I’m not the first person to complain about everything in the mainstream feeling like a repackaged version of something else, and I won’t be the last. And I don’t want to sound like I’m writing off the whole London art scene in my generalisations, because I know there are exceptions. But the feeling of dissatisfaction pervades all the same, and it especially hits home to me when I’m immersed in experiences such as Levente’s concerts.

None of the artists present in that church had big record deals and swarms of fans, nor do I think they expect these things. They certainly didn’t come for the money, since Levente is lucky most of the time if he can cover the costs of travel for the musicians. But they came anyway, and both times I’ve attended these concerts, they’ve played to a full house (or close to).

What I like about these spaces is that, in the absence of financial motivations, you see what is as close to pure creative expression as possible. You experience art and music that exist purely for their own sake, that challenge the audience and sometimes make you feel uncomfortable, agitated, bored or just plain confused—art that falls beyond the pure entertainment most mainstream cultural spaces prioritise.

This is, I think, the difference between what is easy to consume and what requires labour to appreciate. How can you capture the experience of a twenty-minute improvised noise performance in a fifteen-second Instagram reel? You can’t. The quick dopamine delivery mechanism that a rapid-cut cooking video, a makeup tutorial or a clip of someone falling on their ass just isn’t there. There’s no time in that kind of content to stop and ask yourself, “Am I enjoying this?” because before you have that kind of time to form the thought, you’ve probably already gotten your dopamine hit and swiped to the next piece of easily consumable content. And I think this is a huge loss.

When we prioritise quick gratification, profit and digestibility, and also rely on a referential language to categorise art that says “this is like that”, it is to help us quickly understand the art we are about to consume and decide if we think we’ll like it. It’s also for media companies to recommend the next piece of content that is most likely to keep us listening, watching or scrolling. But in the name of this efficiency, we rob ourselves of a more difficult but also more gratifying experience, that of sitting in emotions other than simple pleasure, like discomfort and confusion, and working through them in an attempt to better understand the art we are experiencing.

One of my biggest pet peeves is when I hear people label art as pretentious. While I don’t deny that you can find no small amount of pretentiousness in the art world (some of you will probably find this article pretentious), at the same time I hear it used more and more as a catch-all term for art that is not easy, that does not play into expectations or align with what the person experiencing it already knows and can understand. It is also often used for art that eludes pleasure as the core emotion it aims to elicit. When you label art as pretentious, you close yourself off to it and the potential to learn something that might’ve required greater effort and consideration than passive consumption. Even works that have filled me with frustration or which I felt didn’t earn their difficulty have taught me something about myself, my tastes and my own perspectives on not only art, but also the wider world in general.

It is, inversely, the reason I think we are all talking about superhero fatigue and why deliberately unpretentious films that aim for easy, digestible pleasure often leave us feeling so unsatisfied afterwards, and why they need to be churned out by studios so often. There is next to no labour involved in their consumption, and they do not aim to challenge our understanding of anything. The bad guys are always two-dimensional, the conflicts impersonal, and the solutions to almost every problem are usually as rudimentary as punch, shoot or blow-up. Or in music, we see now that most pop songs are shaped by their first few seconds and produced referentially to other hits, so that algorithms are more likely to recommend them to listeners, TikTokkers will use them in their videos. These are all works crafted for ease, the babyfood of culture that requires no chewing to be passively consumed and digested.

Because we are less willing to open ourselves up to art that doesn’t follow the easy formula of “because you like x, you’ll also like y”, and which doesn’t dare to challenge us beyond easy gratification, more of the mainstream continues to prioritise art and media that have nothing new to show us or say about anything. So we end up in these increasingly bland, homogenous feedback loops of diminishing interest. We consume the same old ideas again and again, except they have less bite, and when they grow stale, we loop back to older ideas that we can repackage and reconsume. It’s why mainstream music is pillaging the nostalgia of the 70s and 80s, since less and less people are willing to seek out music that breaks from convention, and fewer executives are willing to gamble on unknowns that are not easily marketable. These eras fall beyond the lived experience of new markets, so they can be reinterpreted and resold based on style and vibes, while also removing all the uncomfortable social and political context that gave birth to those eras’ best art in the process.

Konsztrukting ELEKTRONIK Soundz EVENING NINETEEN

Which leads me to AI…

During the concert, just as the first waves of staticky noise filled the room and I noticed a couple a little younger than me who’d snuck into the show, an uncomfortable question came into my head that I didn’t have an immediate easy answer to, but which builds on everything I’ve just ranted about.

I was watching these artist produce music largely through settings and processes in machinery and I thought about Brian Eno’s album Discreet Music, which broke ground in the advent of ambient music and was primarily composed generatively—or to use his own words as “automatic music”— through a series of prearranged conditions (and some happy accidents) with tape speeds and loops. It still required the playing of notes on a synthesiser by Eno himself; however, what made the work ultimately such a remarkable piece was the completely unexpected result of his both intentional and unintentional creative process. (Robert Fripp accidentally played it back at half-speed, which ended up being how it’s played on the record.)

The question I started mulling over was this: Is this kind of generative or algorithmic creative process really all that different from prompting something like ChatGPT? I wasn’t immediately sure, but the question was definitely uncomfortable to consider.

I am, on the whole, resistant to AI. I find it a useful tool in the way that a search engine is when I’m researching a topic, looking for reading materials or trying to understand something I have no expertise in. But I’ve also heard far too many conversations with corporate wankers and tech bros who see it as a cash-saving solution for replacing pesky, expensive creatives with an AI system. Or there are the pseudo-religious types who fill the same hole in their lives with AI that they did with crypto, fad-dieting, productivity maxing and any other hokey flavour-of-the month practices.

In short, if you’re saying AI is the solution to all of humanity’s problems, I doubt we’re going to find much common ground. I feel the same sense of looming dread, I think many others do, as this technology steadily creeps with grim inevitability into more aspects of our lives, and I am generally wary of people who rabidly embrace it.

On the other hand, I look at many of the creatives I admire and see in most of them a recurring trend of early adoption for emerging technologies. As I said before, Eno wasn’t the first to go all-in on synthesisers, but he was certainly someone who very early on saw their immense potential and used them to trailblaze. With everything from the printing press all the way to digital cameras and cell phones, there have been those who embrace new technology and its innovations and those who shun them, with the latter seemingly ending up on the wrong side of history more often than not.

What essentially bothered me was that I realised my own feelings about AI were mostly a combination of other people’s opinions either for or against its use in creative practices, but I realised I hadn’t actually sat with it myself and interrogated what I really feel about it, based on my own life experience, perspective and knowledge. As I’ve already said, the pro-AI people make me want to renounce society and go out into the woods to live like a hermit, but the hardcore anti-AI people don’t quite resonate with me either.

So, sitting in this concert hall with my ears full of howling electronic noise, I thought it was worthwhile to really think it through, to look at my initial question and my reservations about AI and see if I could get to the other side of the problem, using the similarities and differences I saw between AI prompting and types of electronic music composition as a comparative tool. If I came out of this process more in favour of AI, maybe it would give me a blueprint for how this new technology could successfully integrate into my art without ruining it. If I came away concluding that AI doesn’t hold the same artistic merit as electronic and generative music, then I at least would have a firmer, more logical reason for why this is a technology I’m not interested in experiencing in the art I seek out, or integrating into my own creative practices.

It’s worth saying before I continue that this is very much a personal reflection rather than an attempt to persuade you one way or the other. If I was trying to be definitive on the topic, you’d be reading a book-length dissertation rather than an article. I don’t doubt some of you will fall very much against what I’m saying here, while others may only agree in part, and that’s all fine with me. The point, afterall, should be to form your own opinions.

AI Versus Generative Electronic Music

A unique characteristic of electronic music, similar to AI, is its almost limitless potential. Most art forms, especially classical ones (oil painting, sculpture, wood carving, playing acoustic instruments), are defined by the constraints the artist encounters in the process of trying to create their art. This could be a painter struggling against their own underdeveloped technique, a cellist whose instrument doesn’t produce the same sound as the Stradivarius they can’t afford, or a writer who struggles to find the time to sit down and focus on a complex project (based on a true story).

To risk a highly general statement, I would say that artistic creation is an attempt at realising an idea through a creative process that combines time, technique and taste/expertise with materials and tools to yield the resulting completed work. There will always be a discrepancy between that initial idea and the result because those factors listed have elements that both enable the creative process and constrain it, and it is in these discrepancies that I think we find that human element, or “grain” as Roland Barthes calls it¹, that makes art resonant and interesting—the failure.

The creative process is just as much a creative struggle against limitation and a failure to fully overcome it. Perfection is boring because it is not natural to us or the world. Failure at perfection is interesting because in it, we see a reflection of ourselves and our constant striving for something more than what we fear we are only capable of. But electronic music flips this paradigm in some ways.

During Covid, in one of those desperate purchases many of us made just to feel something while the world outside seemed like it was ending, I bought a small Arturia Midi keyboard that came with a lite version of Ableton—a music production software. Beyond a few attempts at using GarageBand, I’d never spent any time with a DAW (digital audio workstation) and had no real idea what I was getting myself into. My knowledge of music theory extended as far as a few fuzzy memories from childhood piano lessons, and my technical skill with an instrument was being able to play a few chords on an acoustic guitar—so nothing, really. But for a while by then, I’d found myself daydreaming about composing something and supposing that if I ever made an album, I might have a few ideas about what it would sound like. The creative intention was there, but I had no technical ability or tools to realise it. As a prospective musician, I was so ruled by my own constraints that I wasn’t even able to produce a finished work.

Ableton was unlike anything I’d ever experienced before. Even with the stripped-down entry-level version, there was a head-spinning library of instruments and samples suddenly at my disposal, more tracks than I knew what to do with and a whole host of other plugins, tools and effects that did things beyond my comprehension. After dinner one night, I started messing around with programming drum beats, and suddenly it was almost 3 am, my eyes were aching, and I hadn’t looked away from my screen once in hours as I composed a largely incomprehensible song that fulfilled every stereotype of what shitty EDM and house music sounds like. But I’d still overcome many of my artistic constraints and created a song in only a few hours, having never done so before. It was an incredible, almost intoxicating thought to me that all these ideas I’d had but been unable to realise, might now suddenly be possible.

A lot of musicians and producers these days talk about how the sheer amount of possibilities available to you when composing a song poses its own unique set of challenges in the creative process. It used to be that if you wanted a saxophone on your album, you had to either learn the instrument yourself or find a skilled saxophone player, bring them into the studio and get them on your page before you could record even a second of audio. Now, especially for amateurs such as myself who lack the time, funds and digital dexterity to learn new musical instruments or hire people who know them, what stands between me and a decent saxophone track in my song is a quick download and a bit of time programming in the right notes. It might not be the same as the real thing, but depending on what you’re going for, that’s probably better than nothing at all. Don’t like the sound of your drums? There are hundreds more to try out and play around with until your sound’s just right. Want a full orchestra at your disposal? No problem. Producing in your bedroom, but want to sound like you’re in a professional studio? There are ways to make that happen. If you find music theory and things like chord progressions or melodic compositions difficult, there are also plenty of packs you’ll see advertised online that offer presets, so all you have to do is pick one you like, choose the instrument playing it and then go from there, which tends to be where I and others draw the line in terms of taking the easy path in the creative process. But with a whole world of musical possibilities at your disposal, how do you stop yourself from being overwhelmed and getting lost in a kitchen sink approach to production?

Electronic musician Jon Hopkins talked about how he liked to pick a synth for an album and really let its sound define the work to give it a specific sound and feel. Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt famously developed their Oblique Strategies as a way of getting out of creative jams by using a set of cards with suggestions like “Use an unacceptable colour” to get the mind going and introduce constraints back into a limitless creative ecosystem. All of them deliberately introduce constraints as tools in their own right for artistic creation, rather than already having ones that they are trying to free themselves from.

I find in the prompting process of an AI some similarities to this. With ChatGPT, you are presented with a simple text or voice input field that allows for pretty much any question, idea or request (barring some limitations courtesy of OpenAI’s content policies), and it is up to you to prompt a result by using language to constrain the software’s limitless potential into producing a response that satisfies your request. The clarity of your idea, the specificity of language and the constraints you apply will, theoretically, lead to a successful outcome. Though there is room for variation and unexpected results in that obfuscated process that happens within the AI’s servers, which few of us can fully understand, even as we rely on its results.

Isn’t this similar to what happened with Brian Eno on Discreet Music, where a process of imposed constraints and accidents (or prompts) yielded a work that few would dispute as art? We can reverse engineer how this music was created, but Eno himself didn’t know exactly what he would end up with until he heard the final result, nor could he really claim that every step of that process to make the work was by his own hand. Yet, still, he is the work’s composer.

Like early adopters of AI, many musicians who exist in the electronic sphere of composition have been derided by certain groups as less legitimate than those who play classical instruments. I mean, who hasn’t heard or made a joke about DJs basically pretending to play music while a USB stick of prearranged beats runs through the set? We do tend to have a bias against art of any medium when the resulting work is not produced through analogue processes; even film, we tend to say looks better when it’s shot on, well, film.

But electronic music has, since its early days, only solidified its place in the world of music and fought hard for its legitimacy, with some of its best, like Aphex Twin, moving effortlessly between club music and collaborations with more classical entities like Philip Glass or the London Symphony Orchestra. Will we, in ten or twenty years, see artists who embraced AI in similar places, finally being accepted as legitimate creators?

It’s About How You Use the Tool

Soon before his death, David Lynch was quoted as being unexpectedly open-minded about AI’s role in creativity, likening it to a pencil. The implication was that it is just a tool like any other and that it is the responsibility of the artist to use its creative potential the right way. A pencil is completely benign on its own, but the same pencil in the hands of different people may be used to write the most beautiful poetry or the most hateful condemnations, or just something thoroughly average and forgettable.

I’m not sure I wholly agree with the idea that AI is just as benign because a pencil doesn’t collect data from its users or base its learnings off of stolen intellectual property, however, if we set aside the context of the tool’s corporate baggage and look solely at its application in the making of art, then I think I can find some agreement with Lynch, though I still have my reservations.

A finished artistic creation is the sum of its creator’s concept, technique, knowledge and taste, all of which have worked together over a period of time to realise an initial idea, through materials and tools. It is often argued when people are espousing the virtues of AI, the main advantage it offers is efficiency or a reduction of time in the process of creation, while also widening the scope of what can theoretically be created.

Efficiency and expansiveness are characteristics we can assign to other technological innovations since the printing press. The word processor I’m using right now is drastically faster to use than when I write by hand, then transcribe my writing into said word processor, plus it offers tools such as built-in spellcheck, which previously would’ve required the laborious thumbing through a dictionary. Plus, the internet has made the dissemination of said writing far easier and less reliant on institutional printers, publishers and distributors. Ableton makes creating a song far cheaper and faster than back when you had to book studio space at an hourly rate and hire a sound technician who knew how to record to magnetic tape, after which you’d still have to find a way to mass-produce your single or record and share it, also requiring institutional or at least indie support. Oftentimes, these benefits of efficiency and expansiveness as a result of technological innovation are seen as tools for democratisation and taking the flow of information away from institutions to put them in the hands of the general populace, which is nice in principle, except when this technology sits in the hands of multi-billion-pound corporations, I’m tempted to call bullshit. However, the impact on how we create through the removal of constraints is undoubtedly still there.

While writing this, I started thinking about the first Iron Man film, where Tony Stark is strutting around his workshop, giving Jarvis instructions that are then seamlessly carried out. When watching this, did any of us argue that Tony Stark wasn’t actually the one who created the Iron Man suit? I certainly didn’t. But upon rewatching, apart from soldering a few parts and testing his prototypes, I would argue that the vast majority of the actual labour carried out in his workshop was performed not by him but by his AI.

Stark’s way of engaging with AI software is actually quite predictive of the sort of “ambient application” that AI aficionados talk excitedly about, which seamlessly integrates into our everyday life and is basically universally functional, rather than specialised like the countless apps that clog up our phones these days. Like Tony Stark, will we someday soon be dictating our ideas and needs to an AI that, without difficulty, does whatever we need? Instead of poring over countless settings in a DAW, could I just lean back in my chair and say things like “make the fuzz effect on the bass rougher,” or “rework the drum track so the high hat has more attack”, and it would immediately be done? Quite possibly. And is that any different than a producer lounging on one of those cool leather couches and telling an underpaid technician to do the same? Again, in terms of labour, I would argue no, since much of the labour of producing the song is delegated to someone who essentially operates as an extension of the creative driver, rather than as an autonomous, independent contributor.

I think this question of labour is a really key element to how many of us assess the value of art. Not all great art requires great labour, but I do think the question of who is doing the labour and how successfully it is deployed in the creative process is the more relevant question. Everyone else and I have at least once in our lives looked at a canvas in a gallery that’s just a few splashes of paint, which probably took under an hour to make and scoffed at the extortionate price it undoubtedly sold for. In that case, the argument is that the low degree of labour exerted by the artist is unsuccessful because it hasn’t yielded a work that we find creatively satisfying. Similarly, Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons receive no end of derision (from myself included) for oftentimes putting little to no labour into their art, delegating it to skilled interns and assistants whose own technical abilities are displayed in the fulfilment of a brief they’ve received from the “artist” in question. Or, to bring it back to music, how many times have artists been criticised for not writing their own songs, having minimal input in the way they sound and lip-syncing their performances?

Artistic hackery is nothing new, and in all of those examples, I argue that our issue comes down to the delegation of labour, or the distance between the person who has the idea and the process that leads to the idea’s realisation in a finished work. I also think it has something to do with whether or not we see the fingerprints of human intention in that finished product. In a piece of electronic music or digital artwork made entirely on a computer, I can sometimes still identify the unique voice of the artist behind it. This is the reason Aphex Twin, Jon Hopkins and Flying Lotus will never be confused for each other.

This delegation of labour is where I argue AI differs from past technological advancements, since a printing press still needed an author to write a book, otherwise it would have nothing to print. My word processor still needs me to sit down and actually do the writing, and a DAW still needs a composer to input audio or program beats; there is no song to listen to. Whereas generative AI only needs the prompt, after which point it becomes a supplement for, rather than an extension of, the artist’s own labour. It’s more Koons/Hurst in this way. Even with the most explicit prompting and modifications, you are still essentially outsourcing your idea to an algorithm’s taste and expertise, since whatever it spits out is derived from an amalgam of information that is consumed, homogenised and then distilled into a final result that will only ever be an approximation of the original idea. If you then take the AI’s creation and modify it externally, you start to reclaim some of the artistic labour for yourself, but then, you are only a collaborator, not the sole author.

Our own tastes, whether that’s as artists or simply just as people, are in many ways a product of the influence of external factors—the art we are exposed to, our parents’ tastes, our community’s, etc—however what makes those tastes our own is that they are filtered through our own experiences, knowledge and decisions—our unique perspective, not an AI’s.

Returning to my example with Brian Eno and Discreet Music being created through a partially generative process, the key difference between this and something produced through generative AI is that the album represents the culmination of Eno’s expertise and taste up until that point. No other artist could’ve produced such an album because what made it was just as much the sum of his experiences as it was the immediate conditions of its production, as well as his own openness to his happy accidents. I hear in this album the fingerprints of Eno and the human behind its creation—his taste or “the grain” as Barthes refers to it, which by his definition reminds us as experiencers of music, or art in general, of the human body behind its creation. Even with entirely electronic music where not a single classical instrument was played, I can hear this grain and see in it the voicing of human creativity through tools of expression.

AI’s difference is that, when used as the primary engine for creating a work of art it supplements taste, expertise and technique. It can also be seen as an erasure of these qualities in the artist using it, replacing them instead with its own creative process. It is for this reason that an AI artwork always feels devoid of that human touch and sense of voice, even though it comes close sometimes, and regardless of the human idea that incited it.

I see in it no labour and no creative struggle because the act of labour it exerts to produce its creative output, which may be difficult for a human, is essentially meaningless for it. There is no sweat, no toil, no existential crisis and, just as importantly, no joy, transcendence or interpersonal connection. An artist who sees their work hated or celebrated feels something from that, even if they claim ambivalence. Art is, after all, a dialogue between creator and experiencer, and while AI may simulate dialogue and emotion, it does not experience the catharsis, pathos or bathos of an artist, so it can never be authentic, even if the artist who authored the prompt for the AI may experience something of these emotions.

Does this even matter?

Many who read this may disagree or simply not care. And I’m sure there’s plenty in my train of thought that can be picked to pieces. But it is just that, a personal train of thought as subjective as anything else.

As we continue to move forward into this new realm of technology and art, there will be those who fret about AI’s place in the world, those who embrace it and those who consume it either way, unthinkingly. On Spotify, AI music now saturates the platform and is listened to by countless thousands, if not millions, who either don’t care that it’s not made by a human or remain ignorant of that fact. There will also be artists who embrace AI and those who condemn it and remain steadfast against it.

I think every artist will have to ask themselves what level, if any, of AI they feel comfortable using. I find it extremely useful in the learning phase, but I would never rely solely on the information it provides, use it to formulate the thesis of an article like this one or to draft said article. (I also would defend any inconsistencies or flaws in logic you may identify as the fingerprints of my humanity that justify this whole argument, cheeky as that may be.)

As an example, I have no idea how to write code and have no interest in learning, nor do I have the money to hire a developer. A few months ago, I had an idea for an app and, with the help of AI, was able to mock up a fairly shaggy alpha version. It was far, far from being market-ready, but the idea that soon AI capabilities might get me to a point where I could create something like that through prompting alone was definitely exciting. But at the same time, the fact that I did it this way would probably upset many programmers whose jobs may now be in doubt, just as it upsets me when I hear about companies replacing copywriters with AI bots. Really, if I forced myself to overcome my introverted tendencies and laziness, I could probably have found a programmer out there who was excited by my idea and wanted to be involved, regardless of whether or not I paid them. Together, we might build a collaborative relationship, and the unique ideas, expertise and taste they brought to the project might shift its scope, even making it better off as a result. In our human-to-human dialogue, with all the constraints it presents, I might be challenged to change my initial ideas in a way an AI, which unquestioningly attempts to facilitate my every request, never would.

I think there’s a reason why vinyl music is in the middle of a resurgence, why Floating Points, with an arsenal of digital music creation tools at his disposal, did an amazing collaboration with the London Symphony Orchestra and Pharoah Sanders in 2021 and why I’ve almost never felt an emotional response to an AI image (beyond a vague sense of unease). This reason was summarised beautifully and simply by Rick Ruben when he said, to paraphrase, that in art, as a viewer, I want to see a point of view, which is something only a human can offer. An AI’s point of view is an averaging of every human being that it has processed, homogenised and then selectively emulated, which is not the same as having its own perspective. And without a point of view, art becomes incredibly boring, like talking to someone at a bar who has no opinions of their own, just whatever they’ve been told or read from headlines.

It’s the same reason I find Marvel films incredibly forgettable and why most mainstream music that has been written and produced with a committee behind every decision leaves me feeling hollow and empty. It’s also the same reason much of the highly marketable art I see in galleries has nothing interesting to say to me, or the reels I scroll past on Instagram where influencers use the same gimmicks to sell crap, leaves no impression in my memory. It all comes back to a much deeper and much older question that predates AI but which is essential to how we engage with art as a whole—the question of intention and execution.

For me, the purest form of art exists when the final result stays as true as possible to the initial idea, without muddying or being diverted by outside factors such as commerce, market pressure or attempts to silence the creator(s). Of course, there is compromise sometimes, especially in media such as film and music, where investment is necessary and demands a return. But even so, what you see at the end of the day, what you experience is something that is, at its core, an example of the human expression of an idea.

As I’ve already said, the human is doomed to fail or fall short of that idea, but the exhilaration is in the closeness and the failure all the same. AI is designed and marketed on its ability to achieve fidelity to the human idea. If it is successful, it hasn’t failed in realising the idea given to it to generate, which means that as AI improves, it will paradoxically increase its failure to emulate human creativity, because it cannot, by nature of its purpose, fail. Its lack of constraint, its lack of human fallibility, will be its own downfall in this task and the reason it can never succeed in creating art that is meaningful or authentic.

Sitting in this concert venue, watching two musicians pump almost deafening noise into the room with glee and then, when they finished, being met with applause and cheers from the audience, I felt some sense of comfort.

The lie of AI is that it is unavoidable or something we all must submit to in order to not be left behind. That, I’ve come to wholly disagree with and see as an issue of consent. In the end, I feel that each of us, ultimately, whether as artists or experiencers of art, will have to look within ourselves to answer the question of how AI may fit into our lives (if at all) and what we feel is acceptable to consent to. I have no problem using AI to bypass or fast-track the parts of my life that I try to rush through or take no satisfaction in—like finances or filling in spreadsheets at work. If I never have to do those things again, I’ll be a happy man. And don’t get me wrong, I have seen some artists out there who are producing things with AI that I find genuinely cool, which probably wouldn’t be possible otherwise without massive budgets, soundstages and technological investment. I do not deny that I see in them creativity and a recognisable artistic style. But for me, personally, it still rings a bit hollow and makes little lasting impression in my mind. I’d rather take a deeply mediocre work from a human being, with a few glimmers of artistic spirit, over a hundred immaculately realised AI images, songs or videos any day. I prefer the weirdness, the imperfection and, most importantly, the sense of perspective. I prefer to see labour and failure; limitations that are sometimes overcome and sometimes not. It’s grain, human grain, like the friendly crackle of an old LP or film stock whirring in front of a bulb. There’s warmth and heart there and a living embodiment of the human struggle, which I just don’t find in AI. So while you or others might pay to see the first AI film to hit theatres, might stream some AI band or go to a gallery with images produced entirely by AI, I’ll pass and happily go to some draughty church to listen to some obscure, human musicians, make a whole lot of noise.

- Barthes, Roland. “The Grain of the Voice,” Image Music Text. Fontana Press, 1977.