Category Art

Published August 3, 2025

The Westwood Children, by Joshua Johnson

Loveday Pride at Pusher Gallery, curated by Alexander Bokser and Henry Pride

“The illusion of transparency goes hand in hand with a view of space as innocent, as free of traps or secret places.”

– Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space

To enter Pusher is to cross a threshold rarely noticed in daylight. You slip from Lincoln’s Inn Fields – square & legal – down a crooked stair, past rusted railing and moss-caked wall, into what feels like the under-chamber of the city’s scene.

Here, below the grid, London breathes differently. The air grows warmer, sweeter, more sediment. What was once a basement becomes a grotto, then white cube gallery stage. Down here, beneath the jurisprudence and justifications of empire, the city loosens its collar and dreams in gold plastic and collapsed carnival sets.

The door says pusher – and we are at the gallery: welcome to the romantic underworld of Loveday Pride.

As Susan Sontag observed, “the move from thinking of the city as a battlefield to thinking of it as a body that must be purged, detoxified, cleansed of the impure” reflects a deeper cultural shift – from metaphors of conflict to metaphors of illness. Within that logic, “the city is a cancer: it spreads, it invades, it metastasizes,” Loveday’s materials – protector roll, dust-sheet, emergency foil – tap into that pathology, only to gently rewire it. Here, contamination becomes a precarious craft, and camouflage turns into care.

Pusher Gallery

There’s no white cube sterile neutrality, instead, we are offered layers – of plastic, foil, fresco, fable. Like the Wiltshire smugglers in the Moonrakers myth – whom Pride reimagines in several works – we’re navigating a mise-en-scène of illusion, quick improvisation, and strategic camouflage. What looks like folly is actually tactical.

Pride’s installation Untitled (fresco) is a response to the architectural peculiarities of Pusher’s Lincoln’s Inn Fields basement. A buttery yellow dust-sheet filters the space, softening and distorting both light and intention. This is not the plastic of containment – it breathes, refracts, and seduces. Overlaid with intricate gold drawings stenciled from tablecloths, the surfaces mimic the railings and thresholds of the building itself. Like a site-responsive set, it moves between gesture and sculpture.

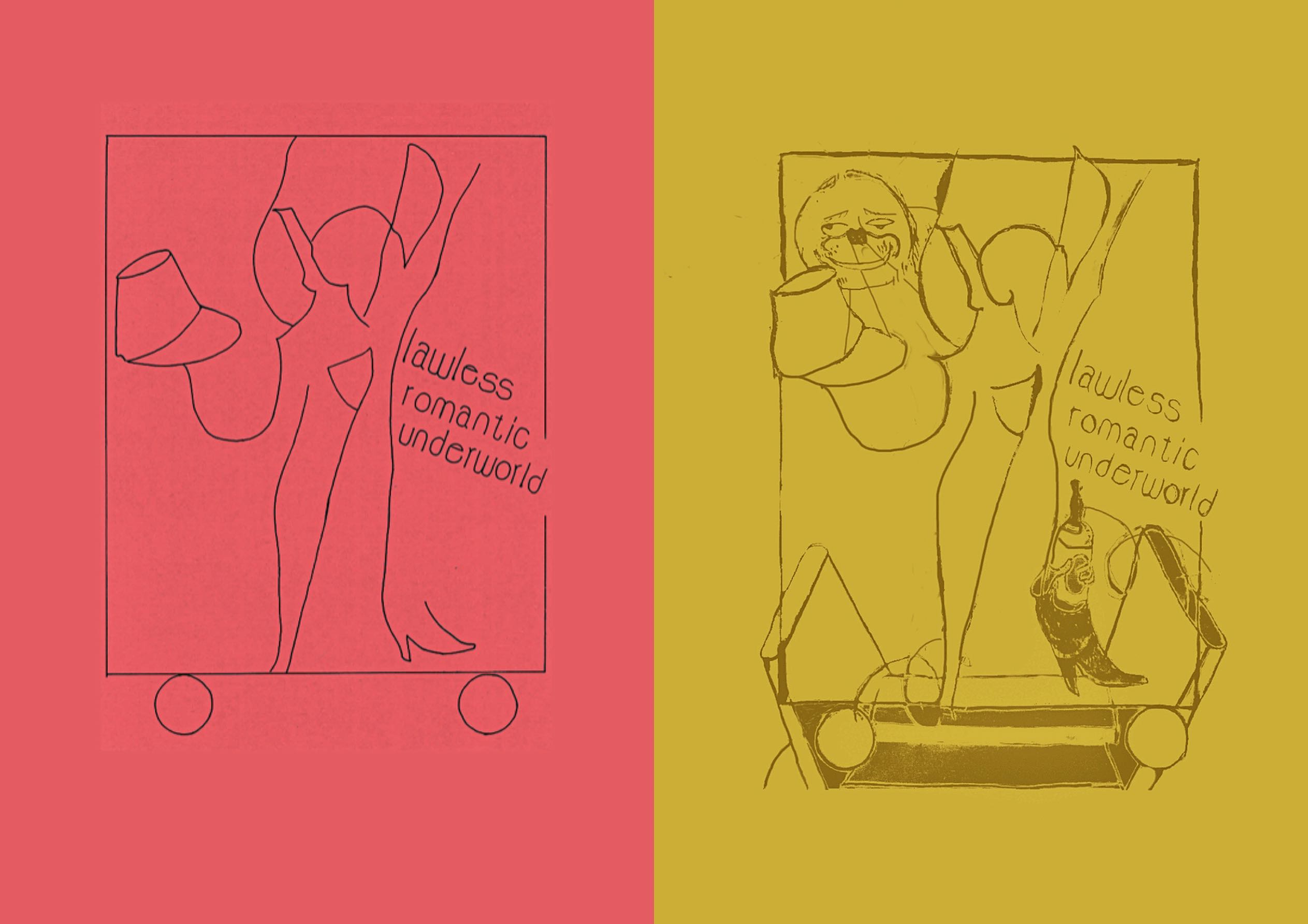

Untitled (Fresco), 2025, Lawless Romantic Underworld by Loveday Pride, Pusher Gallery

Henri Lefebvre’s spatial theory hums beneath all this: the idea that space is not a passive container but something produced – economically, socially, emotionally. Pusher embraces this entirely. Its exhibitions are never passive displays but “tactical jazz” within spatial choreography” – a phrase the gallery has claimed and lived into. Here, nothing is solid, constantly rearranging itself.

Pride’s smaller works – the “desk paintings” – operate like lovers’ eye miniatures. They evoke both carnival and trauma, memory and residue. Emergency foil hides behind calico; a psychedelic swirl is collaged beside a figure with a drill lodged in their head. There is a logic of excavation here. A poetics of emotional infrastructure, as Pride puts it, “I think the figures feel hollow, and still hold weight.”

This is pastoral, yes – but is it idyll? More like Wordsworth ruins of dust-sheet and foil, the exhibition whispers in fugitive languages – carnival, construction, hospitality – synthesised into a material vernacular of protector rolls, stencils, offcuts. The rural, here, is less about escape and more about scavenging: for patterns, memories, structures of care.

The Existential Comic, 2025, Lawless Romantic Underworld by Loveday Pride, Pusher Gallery

Beatriz Colomina, in her theory of X-Ray Architecture, writes about how modern design is haunted by the invisible forces of paranoia and control – the desire to see through, sanitise, expose. Pride’s work resists this pathology. It’s not x-ray but palimpsest. Her materials accumulate, smudge, and mask. They reflect our desire to see through, while gently mocking it.

Ultimately, Pride doesn’t tell us a story. She lets the materials do that (or rather, she lets them withhold it). The shimmer remains under the surface. The moon is a cheese is a barrel. We might be fools – but we’re in on the joke.

“The eye it – cannot choose but see;

We cannot bid the ear be still;

Our bodies feel, where’er they be,

Against or with our will.”

— William Wordsworth, “Expostulation and Reply” (1798)

Lawless Romantic Underworld by Loveday Pride, Pusher Gallery

References:

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991.

Lefebvre, Henri. Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. Translated by Stuart Elden and Gerald Moore. London: Continuum, 2004.

Colomina, Beatriz. X-Ray Architecture. Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2019.

Sontag, Susan. Illness as Metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978.

Wordsworth, William. Selected Poems. Edited by Stephen Gill. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. (Original poems published 1798–1850.)

Pride, Loveday. “Exhibition Notes for Lawless Romantic Underworld.” Pusher Gallery, London, June 11 – July 5, 2025.

Pusher Gallery. “Tactical Jazz Within Spatial Choreography.” Internal curatorial statement, 2024.

Wiltshire Folklore Archive. “The Moonrakers.” Accessed June 2025. https://www.wiltshire.gov.uk/community/moonrakers