Categories Art, World

Published March 19, 2025

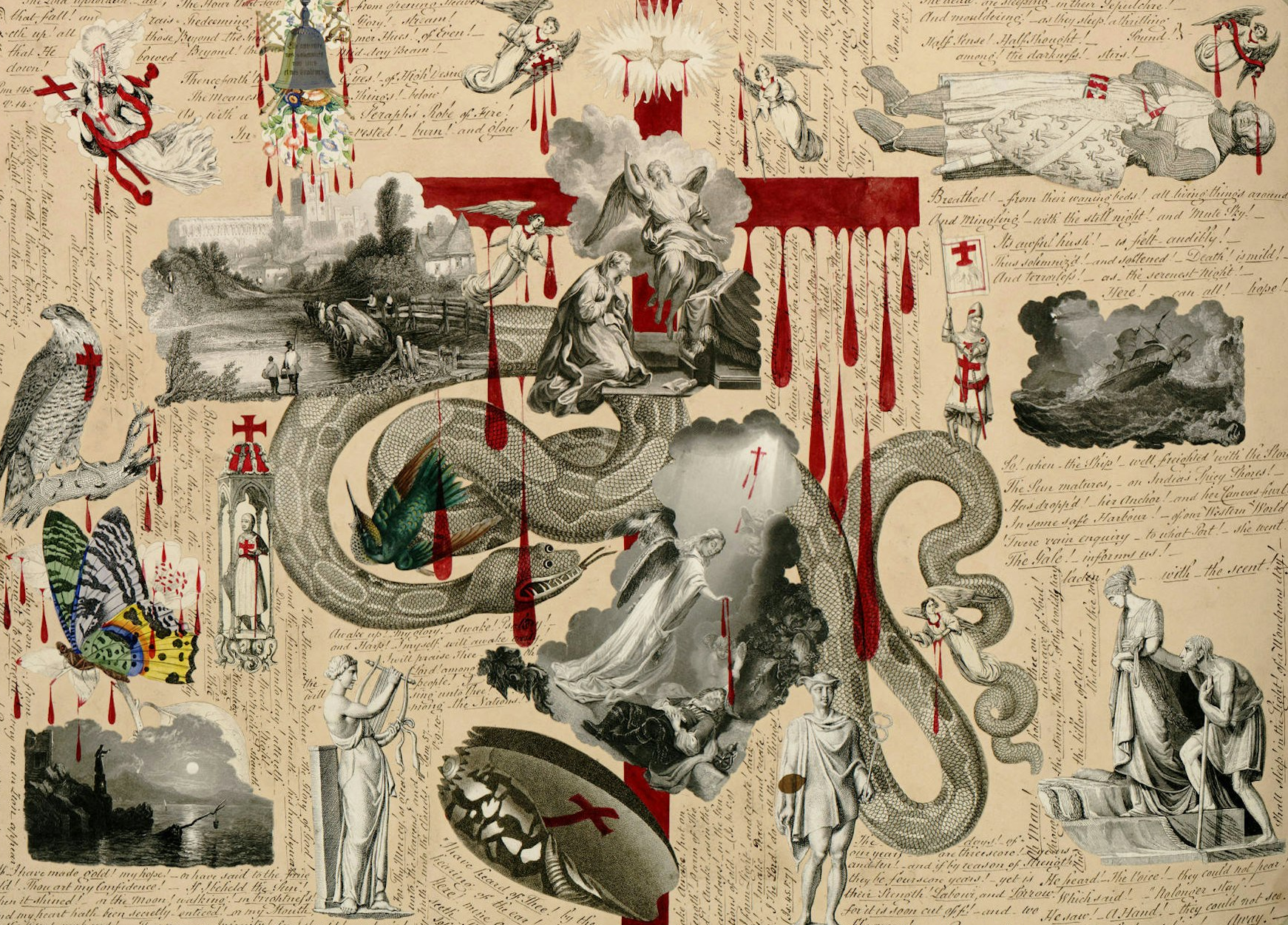

The Blood Collages, by John Bingley Garland

The first time I read Fernanda Melchor was at night. Temporada de Huracanes—or Hurricane Season, as it’s titled in English—was a book I stumbled upon online while searching for horror novels in Spanish. I had no idea what it was about, only that it had been nominated for the 2020 International Booker Prize.

Reading the first pages felt like a heavy slap straight to the face. I wasn’t ready for it. There were no paragraphs, no full stops—only commas scattered like gasps between dialogues and descriptions. Sometimes, they weren’t enough to help me grasp who was speaking. Melchor’s narration jumped from character to character, story to story, without warning. It was disorienting, almost dizzying, and it took me some pages to get used to it.

I regretted recommending it for a book club with friends and a few people I barely knew. Not just because of its fragmented style but because of its content. It was filthy, unsettling, chaotic. I was scared it would be too much, luckily, they all seemed to have enjoyed it, as they said on the reunion at a café. One boy who had lived in Mexico told us how real it all felt, from the language Melchor used to some of the characters and sets.

— “Te lo juro, lo es. Hay lugares donde la violencia y la pobreza están demasiado presentes. No te estoy jodiendo, no es cuento, es lo que pasa.”

I couldn’t stop reading. The book gripped me in a way few others had, pulling me back to its pages at all hours. I didn’t want it to end, so I took my time, trying to absorb every word— new words since much of the language was drenched in Mexican slang that I didn’t know, but it didn’t keep me from understanding it all. I remember reading it on the bus to university and suddenly stopping, afraid that someone might glance over my shoulder and catch a glimpse of what I was reading, stripped of context. I closed the book and stared ahead, letting its rotting imagery unfold in my mind instead.

Temporada de Huracanes was a turning point. From there, I discovered other Latin American writers exploring similar themes—Mónica Ojeda from Ecuador, Mariana Enriquez from Argentina, Dahlia de la Cerda from Mexico, recently nominated for the 2024 International Booker Prize. There was a whole movement happening, and I hadn’t even realised it.

I devoured every book I found, following recommendations from Goodreads, literary blogs, and even the authors themselves. Each writer had a distinct voice, a unique way of shaping their stories—whether through short fiction, novellas, full-length novels, or even collections of fictionalised chronicles. But they all shared one thing: violence.

Since childhood, fictional violence had fascinated me—the thrill of the forbidden, perhaps. Horror movies, horror books, horror, anything. I started writing short horror stories at a young age, and at ten, I launched a YouTube channel where I uploaded homemade horror films, shot on my family’s handycam. I found comfort in the controlled fear of horror. I knew that outside the stories I was consuming or creating, nothing was actually wrong.

As I got older, my focus shifted from ghosts to humans—the unravelling psyche, the slow decay of consciousness. But even then, it still felt contained, rooted in fiction. At some point, though, that distance started to feel artificial.

What drew me to Melchor, Ojeda, and Enriquez was the absence of that control. My only possibility was to read their work, to sit with it, to stay inside it. There was no relief, no safe distance—just a relentless, oppressive atmosphere that didn’t let up even after I put the book down. It unleashed a sense of addiction in me; I wanted to know more, to see how far the authors could take their stories, how much they could push my boundaries. It felt like an instinct, an urge I couldn’t suppress. At some points, curiosity really did kill the cat.

Literature, like journalism, has a way of exposing the worst in the world, and these books were no exception. Watching the news, no matter how brutal the images, there’s always a screen—a barrier that reminds you that you are an observer. And when the screen turns off, the images fade. But in literature, there is no off switch. The characters, the events, stay with you. And maybe that’s natural—our empathy runs deeper when the people we read about feel real when they no longer seem like strangers.

Some of their works lean toward realism, others flirt with the supernatural, but what sets them apart is their grounding in reality. Real places. Real acts of violence.

Mariana Enriquez’s Bajo el agua negra is a prime example. The story deals with police brutality—particularly against society’s most vulnerable—a long-standing issue in Argentina. Since the fall of the military dictatorship in 1983, police violence against young people has only escalated. The story is inspired by a real case in which officers forced two boys to swim in a heavily polluted river filled with industrial waste. In Enriquez’s version, their bodies never resurface. In reality, they did. The case became a national scandal, and Enriquez didn’t want to write a journalistic chronicle—she was reliving a memory.

That’s what makes Mariana Enriquez’s work so haunting. The horror isn’t confined to the supernatural; it seeps into everyday life. That was what unsettled me the most—it made me profoundly uncomfortable. Probably in the same way my horror-averse friends must have felt at thirteen, walking out of the cinema after the first scenes of Evil Dead. It wasn’t a sudden revelation but an intensification of something I had always been drawn to: the raw, unfiltered brutality of real-world violence, now stripped of the comforting distance of fiction. As a journalism student, I have never been naïve about the world’s horrors. But these books brought that reality even closer, I felt.

Stories of abuse, of violence against women and children, where the supernatural horror almost felt like a relief from the weight of it all. And yet, I kept reading. I kept searching for that discomfort, that rawness that had first unsettled me on a late-night reading of Temporada de Huracanes. Because once you recognise horror not as something lurking in the shadows but as something deeply embedded in the world around you, it becomes impossible to unsee. Literature doesn’t create that darkness—it only forces us to confront it.